Anthony Colin Bruce Chapman, CBE (19 May 1928 – 16 December 1982) was an influential English design engineer, driver, inventor, and builder in the automotive industry, and founder of Lotus Cars.

His only one entry 1956 French Grand Prix – dns. Info from Wiki

Motorsport memories: Colin Chapman, the driver

By James Page

Denis Jenkinson was not a man who was liberal with his praise.

Anyone who received a good word from the revered Motor Sport correspondent must have truly earned it, which makes it telling that – in his superb 1958 book The Racing Driver – there is a photograph with the following caption…

‘A designer who can drive a racing car is worth his weight in gold, and here we see Roy Salvadori telling Peter Berthon all about the BRM car the latter has designed. In the centre is Colin Chapman, unconvinced of Salvadori’s story, having just driven the car, and about to redesign the suspension for the Bourne concern.

‘Chapman is one of the few racing car designers who can drive fast, and it is a moot point whether his ability as a racing driver is not better than his designing ability, but both are of an extremely high standard, so he has little need of drivers, other than as competitors.’

Chapman campaigning the Lotus Mark I in which he enjoyed success

Jenkinson was writing shortly before Chapman fully devoted his formidable brain to Formula One success with his own Lotus company.

Yet to come were the monocoque 25, the Cosworth-powered 49, the wedge-shaped 72 and the ground-effect 79 – championship winners all, those and countless others establishing him as one of the greatest designers in motorsport history.

It’s for masterminding such cars that he’s best remembered, and Chapman himself played down his driving talent – but clearly there was plenty of it.

He maintained that, in the early years, he drove his cars simply in order to uncover their faults. The challenge was not in being a better driver than the next man, but in designing a better machine.

That attitude went right back to his trials days, as well as the Mark III that dominated 750 Motor Club events. It was his success in the Mark III, in fact, that led rivals to ask him to build them one – and hence Lotus was born.

As his engineering reputation grew during the 1950s, Chapman carried out work for the likes of Vanwall and, as Jenkinson mentioned, BRM.

Having designed a spaceframe chassis for Vanwall, he was then recruited to drive for the team at the 1956 French Grand Prix. Unfortunately, he managed to crash into teammate Mike Hawthorn during practice and didn’t take the start.

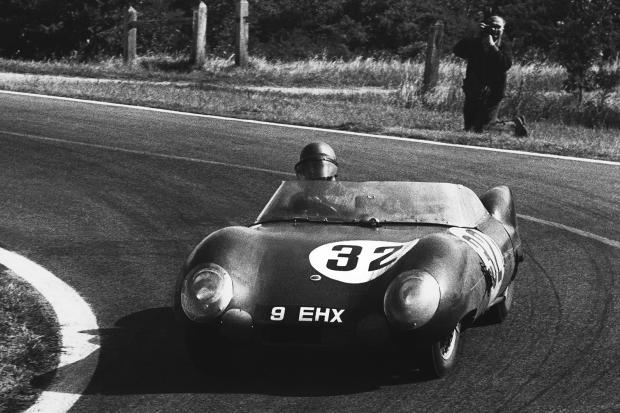

Taking on Le Mans in the Lotus MkIX in 1956 (left) and the following year in an Eleven

He had more success at the wheel of his own cars, though. He twice drove at Le Mans, sharing a MkIX with Ron Flockhart in 1955 (top of the page) and an Eleven with Herbert Mackay-Fraser in 1956.

He failed to finish on both occasions, but during those two years chalked up numerous victories in national events, at everywhere from Aintree and Snetterton to Goodwood and Silverstone.

Perhaps his best-known success came at Brands Hatch in late 1958, purely because the man who finished second was to prove central to Lotus’ enormous success over the next 10 years. Scottish team Border Reivers was interested in buying a Lotus 12 for one of its rising stars, so a couple of months earlier Jim Clark had travelled down to Brands in order to test one.

His friend and mentor Ian Scott Watson went with him, and was smitten by the new Elite that Chapman also had there. He ordered one to race in 1959, and when told that it would be ready in time for the Boxing Day meeting, he and Clark once more travelled south.

They picked up the car that morning and drove it to Brands. It was Clark’s first race at the Kent circuit, and he’d be up against the Elites of Chapman and Mike Costin. Before the start, the young Scot was unimpressed to hear the two men discussing which of them would win.

In his autobiography, Jim Clark At The Wheel, he described how it turned into a ‘whale of a dice with Colin’. He admitted not knowing much about driving round Brands at that point and wrote: ‘If I had known what I know now I wouldn’t have done half the things I did in that race.’

The two men went at it hammer and tongs, but towards the end Clark built a slender advantage. Only when a backmarker spun in front of him at Druids was Chapman able to slip past once more and take victory.

Little more than a year later, and having campaigned Scott Watson’s Elite throughout 1959, Clark signed for Lotus to drive in Formula Junior and Formula Two.

Clark leads Chapman at Brands Hatch on Boxing Day 1958

As his company went from strength to strength, Chapman inevitably had less time to go racing himself, but he did appear in a support event for the 1960 British Grand Prix. Having apparently expressed an interest in a 3.8 Jaguar Mk2, he was offered the chance to take part under the guise of a highly competitive ‘test drive’.

A spectating Innes Ireland – who was a factory Lotus driver at the time – remarked that he’d be out of work if his boss crashed, but Chapman was on supreme form and won by a nose from tin-top specialists Jack Sears and Gawaine Baillie.

Eleven years later, BBC television viewers who were more used to seeing Chapman’s creations winning Grands Prix got to appreciate his abilities as a driver.

Opening proceedings at the 1971 World Championship Victory Race was a 10-lapper for team managers on Brands Hatch’s short circuit.

All of them were aboard Ford Escort Mexicos and, predictably, Jack Brabham and John Surtees lined up on the front row, but between them was Chapman, who’d set the second-fastest time during practice.

Story has it that, in the weeks before the race, the ever-competitive Lotus boss tried to borrow a colleague’s Mexico so that he could get in some practice at Hethel. Said colleague didn’t like that idea, so instead Chapman sourced one from a Ford dealer.

There were further mutterings that, following practice, Tony Rudd was seen with his head beneath the bonnet of Chapman’s car…

Stirling Moss was one of many big names Chapman proved himself against – here they’re at Oulton Park in April 1956

At the start, Brabham streaked into the lead ahead of Chapman and a fast-starting Frank Williams, who soon dropped behind Surtees again after an off-course moment at Bottom Bend. Williams then spent the rest of the race locked in battle with March boss Max Mosley.

With Emerson Fittipaldi urging him on from the pit wall, Chapman started to pull away from Surtees and reel in Brabham. In the commentary box, Barrie Gill was joined by Graham Hill, and the former Lotus ace was on fine form.

“I’d put money on the fact that the cars will touch,” he said as Chapman drew ever nearer, “and by touch, I mean thump each other.”

With four laps to go, Chapman and Brabham surged through Paddock Hill Bend side-by-side, prompting Gill to remark: “Chapman’s very brave, isn’t he?”

“He certainly is,” came the reply, “I’ve seen him fly as well…”

Going into the final lap, the two cars were locked together, and Gill suggested that Brabham would be looking in his mirror more than he was looking forward.

“Highly unlikely,” said Hill. “I’ve never known him to use his mirror at all.”

Into Paddock for the final time, Chapman moved to the outside, then cut across and dived inside Brabham to take the lead. Cameras at Druids caught the huge smile across his face and he looked set for victory.

As he went to change into top exiting Clearways, though, there was a puff of smoke and not a gear to be found. Brabham was through in an instant and, as Chapman coasted towards the line, Surtees also flashed past. The fact that he’d set fastest lap was presumably little consolation.

Chapman is remembered as an engineer and team boss with famous drivers such as Clark and Andretti, but his own driving skill shouldn’t be forgotten

Chapman was by no means the only designer or engineer who was also a top-level driver. Before the war, Rudolf Uhlenhaut was equally versatile.

‘Uhlenhaut will frequently put on a pair of goggles,’ wrote George Monkhouse in Motor Racing with Mercedes-Benz, ‘leap into the driving seat, and roar off round the circuit at a tremendous speed during practice, just to satisfy himself that the cars are working properly.’

He also used to test cars on the autobahn at Bruschal, which was not far from the Mercedes factory.

It was an ability that must have given both him and Chapman a greater appreciation of a driver’s feedback – Fittipaldi once said that Chapman was a master at interpreting his comments and applying them to the car.

So amongst all the plaudits for his designs, remember too his formidable talent behind the wheel. Yet another string in the bow of a remarkable man.

Images: Motorsport Images/The Colin Chapman Foundation

Gallery Other