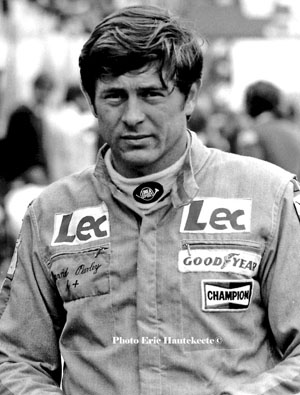

David Charles Purley, GM (26 January 1945 – 2 July 1985) was a British racing driver born in Bognor Regis, West Sussex.

He participated in 11 Formula One World Championship Grands Prix, debuting at Monaco in 1973. Info from Wiki

Bio by Stephen Latham

David Purely will certainly never be a ‘forgotten’ driver due to his heroic actions in attempting to rescue Roger Williamson at Zandvoort. However he also survived a crash which was considered the heaviest impact a human being had ever survived (the car and him decelerated from 108mph to 0mph in just over half a metre) and then faced months of agony in recovering from it.

David Purley started out working for his father Charlie’s LEC Refrigeration company but left after a huge row with his father. He then became involved in demolition work on buildings in London and when that finished he joined the Coldstream Guards. During his training, on one occasion he came down sitting on top of the instructor’s parachute when their chutes became entangled. He was eventually sent to Aden with the First Parachute Battalion and frequently encountered mortars, grenades and machine gun fire.

While still in the army, he was introduced to motor racing by his neighbour, Derek Bell. He shared an AC Cobra with a cousin but wrote it of at Brands Hatch though returned the next year with a Chevron B8.

After leaving the military, he set up his own F3 team and after a slow start scored a hat-trick of wins at Belgium’s Chimay circuit in 1970. Chimay was a fast, dangerous, circuit which used to get his adrenaline going and he stated that he always drove faster when he was slightly nervous as it gave an edge to his driving.

At his F2 debut at Oulton Park in 1972, he took pole position (though his throttle cable broke during the race) and other results that year included third place at Pau and a Chimay F3 victory.

For 1973, a March 73B was bought to contest the two British Formula Atlantic Championships. He was leading both Championships but finally finished runner-up in the Yellow Pages series and retired while leading the final BP round.

A deal had also been made with March for several drives in F1 and he managed to qualify for Monaco though at Silverstone he crashed his car and had to withdraw. The third GP was at Zandvoort, which was totally overshadowed by Roger Williamson’s horrendous accident and David’s attempt to rescue him. He was subsequently awarded the George Medal for his heroism though he downplayed his actions, saying it was purely a reflex action and the natural reaction of a man who had spent time in the armed forces.Most people will remember David’s actions at Zandvoort and his anger and sheer helplessness at not being able to rescue him.

Following this was the German GP but he had to face the pressures of constant publicity following Zandvoort. In practice, he was extremely slow and could have been excluded but the other drivers signed a petition urging the organisers to allow him to start regardless of his time. He began the race slowly but got quicker and quicker and got back into his usual pace, finishing fifteenth. At a later race at Monza he finished ninth.

In 1974 he raced March and Chevron cars in the European F2 Championship, against drivers such as Depailler, Jabouille, Pryce, Stuck, Laffite and Tambay and with second places at Rouen, Salzburgring and Enna, Purley he finished fifth in the series. He then formed his own team to run in F5000 and in 1976, and six wins, a second, two fourths and a fifth saw him take the ShellSport Gp 8 Championship.

Plans were made to move to F1, and though the team was run on a tight budget, in his LEC CRP 1, he finished thirteenth in Belgium, fourteenth in Sweden and there was a sixth place finish in the Race of Champions. At Zolder, he led for half a lap before pitting for slick tyres though the gamble didn’t work as it kept raining. Nicki Lauda mistakenly thought he had been impeded by him and angrily complained about ‘rabbits’ in F1; David’s answer was to turn up at the next race with a rabbit painted on his cockpit side though Lauda in return had a ‘super rat’ sticker on his visor at the following race.

For the British GP at Silverstone, he had to take part in a pre-qualification session and during it the throttle jammed open and he went straight into the barrier at Becketts. The car folded around him as it stopped from 108mph in just 26 inches and suffered deceleration which briefly touched 180g. The impact stopped his heart but a doctor revived him and in shock he began to argue with his team manager about the cause of the accident. He was cut out of the car and then driven by ambulance to a nearby hospital though was not expected to survive the 20 mile journey.

At that time, the accident was considered the heaviest impact which any human being has ever survived and he featured in the Guinness Book of World Records.

Following this David suffered constant pain for six months but during that period he took part in some Porsche 924 races to see how his driving standards were.

The accident meant his left leg was one and a half inches shorter than his right and his ankles were so badly damaged that he would never be able to run again. However, he would eventually resume racing, driving the Lec and a Shadow DN10 four times in the Aurora British F1 Championship. He took a fourth place finish at Snetterton and when he returned to the pits he was in so much agony he had to be lifted from the car.

Concerning his injuries, in an attempt to lengthen his shortened left leg, he found a Belgian surgeon who was prepared to undertake an operation to break it, stretch it by a millimetre a day, and then graft in bone. However, he was warned that the pain would be greater than anything he had ever experienced and if it failed, it would leave him permanently disabled. He took the brave decision to go ahead, knowing he would be months in hospital in agony and perhaps never being able to walk again.

But he did walk again, and went on to race in Enduro motorcycle races and compete in competitive aerobatics in his Briggs bi-plane. Sadly, in July 1985, while in his plane, he was killed when a technical fault caused it to crash into the sea off the West Sussex coast.

Nice memory of Nick Taylor for David Purley:

The snowy oulton Park meeting in 1975. I remember it well. I lived about an hours walk away and set off with a mate with our lunch which consisted of a block of jelly and a flask of cold orange squash (not ask me why we thought this was a good plan). As it was snowing we were absolutely freezing. remember John Noakes was there filming go with Noakes. As we sat in the old canteen we were approached by David Purley who could see how ill prepared we were and bought us a cup of team each. He did offer to buy us some food but we politely refused even though we were starving. I went back the following day for the race in the relative comfort of my dad’s Morris Minor and took a few photos. I’ve often thought about this day were I see articles/photos of David. Great guy, great memories.

In 1970 Bell came home from Ferrari and Church Farm teamed up with Tom Wheatcroft. They bought a Brabham BT30, two FVA engines, an old Bedford truck and did the European F2 championship, winning in Barcelona and threatening the big works teams. At the same time Derek was driving a Porsche 917 for Steve McQueen’s Le Mans movie, revelling in the big sports car. It was back down to earth a year later when Earle and Rodney Banting decided to start BERT — the Banting Earle Racing Team — running Patrick Dal Bo’s F2 Pygmees for, among others, Carlos Pace. “The car was good but the money ran out and we packed it in halfway through the season.” At this point along came David Purley.

“It’s been well documented but the time with David was a huge experience in so many ways,” he says. “He was an extraordinary bloke. I dropped in at Goodwood one day and there he was, testing his Atlantic car. I’d never met him, though we both lived in Bognor. I suggested a few tweaks to the car and he went quicker. He thought that was great, and so there I was working with him at the next race. Then Greg Field and I put together a programme for him with money from his father’s Lec refrigeration business. Greg and I set up a workshop in an old chicken shed behind the factory in Bognor, and we did two seasons with a Chevron and won the Group 8 championship in 1976. We made lots of bits for that car — new wings, side radiators, things like that — and Derek did a lot of the testing while David was away on the Tasman series.

“Then Charlie Purley, David’s father, said he’d pay for us to do Formula 1. Well, we had no idea what that might cost, and there was just me, Greg, two mechanics, a machinist and Ken Horden, who built our DFVs and ran them on a dynamometer in the shed. Anyway, we hired Mike Pilbeam who’d left BRM, old man Purley gave us access to the ‘special products’ area of his factory and they made the bits from Pilbeam’s drawings. That’s how we made the car, CRP 1. The first time David tested at Goodwood he stopped after 50 yards and said to me ‘it’s broken in half, it’s dragging along the ground’. I told him that was the skirts, some plastic bits we’d added when the rules changed. So he did 10 laps, came in, and said it was all fine. He hated testing.”

Purley took sixth on his debut at the 1977 Race of Champions. “All the F1 teams were there. I think the laughter drowned out the noise of the car, but we struggled through the season and at Zolder we got lucky. We kept David out in the rain while everyone came in for tyres and he took the lead. We thought, OK, this F1 is easy, but then Lauda came up behind him on new tyres and David held him up. They had a bit of an argument about that afterwards. People said we’d made an inspired decision, nearly pulled it off. But the fact was with only three of us in the pits we realised we couldn’t do a tyre stop, and when he did come in it took about half an hour to change the damn things.”

Then it all went wrong at Silverstone. The DFV’s throttle stuck open, the car ploughed into the sleepers at Becketts, and Purley spent the rest of the year recovering from horrible leg injuries. But neither he nor Mike considered giving up. They built a new car and Purley came back, did an Aurora race, and then called it a day.

From Joe Saward www.joeblogsf1.com

Charles and Frank Purley sold fish before taking over a small electrical repair business which they turned into the Longford Engineering Company Ltd manufacturing munitions at a facility on Longford Road in the seaside resort of Bognor Regis on the south coast of England, not far from Chichester.

It was a profitable but rather short-term business because when the war ended in 1945, the company needed to find something else to do, so they began experimenting with refrigerators and manufactured their first fridge in 1946. They were soon doing so well that they bought a new site on the Shrimpney Road, where they built a mass production facility in 1947. Today the factory site has been turned into a large supermarket and car park, but there is a nod to history with the access road, known as Fridge Way.

They changed the name of the company to LEC Refrigeration at the end of 1954 and this expanded quickly, becoming a public company in 1964, generating millions every year. They were making so much money that they bought 50 acres of land and built their own landing strip, known as Lec Airfield. Charles son David was born at the end of the war. He attended a couple of boarding schools, being expelled from one before becoming the Lec company pilot for a few months before falling out with his father and going to work as a member of a demolition gang, working on tall buildings. He then decided that he join the army and signed up at a recruiting office. He spent two years at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst before being commissioned in December 1966, and joining the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment early in 1967 as a 2nd Lieutenant. He survived a close call during training when his parachute became entangled with that of his instructor and he rode his way to the ground on the top of the other instructor’s parachute. Later that year he was sent to Aden where he spent several months in action against rebel forces. While still in he army he was introduced to racing by a neighbour Derek Bell and bought a powerful AC Cobra sports car, which he would soon write-off at Brands Hatch. He then bought a Chevron sportscar and decided that racing was more exciting than soldiering and resigned his commissioned at the end of 1969 and set up his own Formula 3 team with a Brabham BT28. The team was funded by the family and called Lec Refrigeration Racing. He won his first F3 victory after just a few weeks, beating James Hunt by a tenth of a second in the Grand Prix des Frontieres at Chimay in Belgium. He would not win again until he returned to Chimay a year later.

In mid 1971 he switched to an Ensign and his results improved and he won two races in Britain at the end of the year. For 1972 he concentrated on Formula 2 with a March 722 and finished third at Pau, but he returned to Chimay to win his third consecutive Grand Prix des Frontieres.

He switched to Formula Atlantic in 1973 but made his F1 debut that year at Monaco in a March 731. Later that his efforts to save Roger Williamson from a burning car at the Dutch GP led to the award of a George Medal for bravery. He left Formula 1 and spent 1974 racing in Formula 5000 and became increasingly successful and won the British title in 1976.

That winter he commissioned designer Mike Pilbeam to build a Lec F1 car nd in 1977 qualified for several Formula 1 races. In practice at Silverstone he suffered a stuck throttle and crashed with incredible violence. His life was saved by rescue crews at the scene of the crash but it took many months for him to recover from multiple fractures to his legs, pelvis and ribs. He did eventually have a second Lec F1 car built and did one or two events and then raced a Shadow in the 1979 British F1 series but then he quit racing. He underwent a series of painful operations to try to repair his damaged legs and then settled down to run the family business – and to do aerobatics in his spare time. In the years that followed he survived two crash landings, but in the summer of 1985 his Pitts Special stunt plane went down in the sea, off the coast. It was an accident that even David Purley could not survive.

Gallery Other F3 and F Atlantic F2 F1 F5000

1973 Dutch GP Zandvoort

Interview with Ben Huisman

Ben Huisman, the 1973 Dutch Grand Prix race director on the circuit of Zandvoort. He tells his story to researcher Nando Boers for Dutch VPRO televison.

Interview with Herman Brammer

Herman Brammer (1944) was a marshall waving the yellow flag on the race track to warn coming drivers for the accident of Roger Williamson back in 1973. He tells his story to researcher Nando Boers for Dutch VPRO televison.