Leslie George Johnson (22 March 1912 – 8 June 1959) was a British racing driver who competed in rallies, hill climbs, sports car races and Grand Prix races.

Johnson raced Delage, Talbot-Lago and ERA cars in single-seater events between 1946 and 1950.

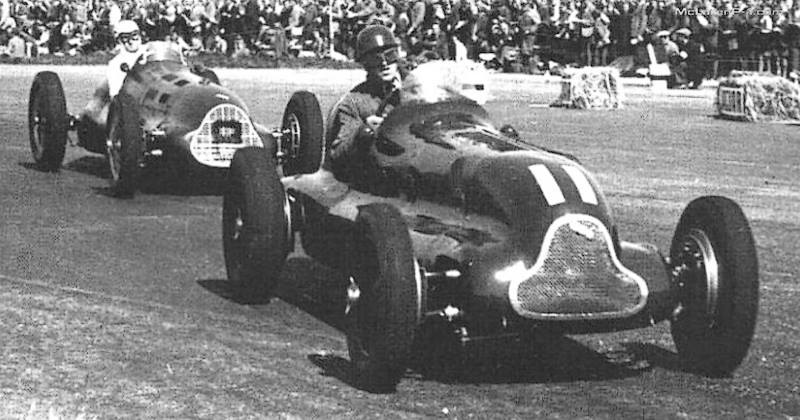

In 1950 Johnson again found himself repeatedly sidelined by the car’s unreliability: DNF, British Grand Prix, Silverstone. Started from the fourth row. The supercharger disintegrated after two laps and the car caught fire.

Other outings ended in steering failure and another split fuel tank. Info from Wiki

Bio by Stephen Latham

Although he only contested one World Championship Grand Prix, Leslie George Johnson excelled in sports cars plus also competed in rallies and hill climbs. He specialised in European sports car endurance events, competing in five Le Mans 24-hour races, two Spa 24-hour races and four Mille Miglias. He also took part in five Grands Prix, and broke several world speed records for production cars but although he proved a talented driver, business interests were his primary concern. Also, as a child his heart and kidneys were damaged by nephritis and acromegaly and as his health in adulthood deteriorated it put restrictions on his racing. His business ventures included the acquisition of British racing car manufacturer English Racing Automobiles (ERA) after World War II and he also initiated and negotiated Stirling Moss’s first commercial sponsorship deal, with Shell.

Born on the 22nd March 1912 in Walthamstow, North East London, his father was a cabinet maker though died soon after starting his own business. Despite only being in his teens, Leslie had to support his mother and younger brother so took charge of the firm and the company thrived and became a successful furniture manufacturing business. His racing started in the 1930s when he rallied a BMW 328 and he was winner of the Scottish Rally and the Torquay Rally in 1938 plus third with it in 1938 and 1939’s RAC Rally. In 1939 he also raced a Frazer Nash at Crystal Palace in July and August and was fifth in the Crystal Palace Plate and second in the Imperial Plate.

After the War, when competition resumed he progressed from rallies to hill climbs, sports car racing and single-seaters. A member of the Rootes factory team, he also rallied an XK120 before progressing to sports car racing, In 1946 he competed in reliability trials with the 328 and was second with it in a sports car race at Brussels though retired from the same meeting with a Talbot-Lago T150C due to gearbox problems. He also achieved the fastest lap at Brussels and The Motor described his performance as that of ‘a budding Dick Seaman’ and added that “Sommer and Louis Chiron danced with fiendish glee as Johnson took the esses in a single controlled slide. Chiron said he had the flair of Nuvolari. Sommer, inarticulate with emotion, kissed the poor chap.”

He competed in a number of speed hill climb events in 1946 and with the Talbot Lago T150C and the BMW 328 was first and second at Shelsley Walsh’s Speed Hill Climb International meeting. He was fourth and fifth at a Bugatti Owners Club Prescott Speed Hill Climb plus took second with the Talbot at the Bugatti Owners Club Prescott Speed Hill Climb. Further events with the Talbot saw a win, fastest time of the day, and a course record at the Scottish Sporting Club’s Bo’ness Speed Hill Climb (on his first time at the course) plus third in class at the Jersey Motor Club Bouley Bay Speed Hill Climb.

He raced single seaters between 1946 and 1950 and in August 1946 broke the lap record at the Ards circuit in Ulster. However, at Ulster, the clutch failed to release at the start so the car had to be pushed off the line but he worked his way up to fourth (behind Prince Bira, Reg Parnell and Bob Gerard) until a melted spark plug finished his race four laps from the end. There were races in 1947 with an ex-Louis Chiron Talbot-Lago T150C and he used it as a sports car and a single-seater, simply removing the mudguards to convert it to GP configuration. He was sixth in the Jersey International Road Race and seventh in the Belgian GP at Spa though retired from the Empire Trophy right at the start of the race. At Bremgarten in Switzerland, due to a lack of crowd control, Achille Varzi’s Alfa Romeo killed a spectator on the track during practice and Leslie withdrew from the race after his Talbot-Lago locked a brake entering a corner and the car’s swinging tail hit some spectators, tragically killing two. There was a planned entry with John Eason Gibson in the Mille Miglia though they did not attend but he raced in the Empire Trophy and had a class win at Prescott Hillclimb.

During this time he acquired English Racing Automobiles (ERA), together with one of their prewar ERA E-Type single-seaters, but though the car was fast it proved fragile. He had a fifth place finish (plus fastest lap) in the Empire Trophy, though at the Grand Prix du Salon, at Montlhery, after taking pole position and the lap record his fuel tank split in the race and at 1948’s British GP he unfortunately had to retire after it broke a driveshaft on the first lap. At the Paris 12 Hours, the BRDC entered a British Team, which included a Healey Saloon (GWD 42) driven by Leslie and Nick Haines. An impressive start saw them take the lead on the first lap but while running in ninth place and with only 40 minutes remaining, the Team prize was by now guaranteed for the BRDC so their car GWD 42 was withdrawn. He finished third in the Manx Cup in an Alvis though a highlight came when he achieved Aston Martin’s first postwar international victory, taking the Spa 24 Hours with St.John Horsfall in a DB1.

He is most closely associated with Jaguar, particularly the XK120, and his various successes included the model’s first-ever victories in Europe and the United States. In 1949 he won Silverstone’s Daily Express International Sports Car Race, despite an early collision with a spinning Jowett Javelin which dropped him back to fifth place. Then in 1950, in the XK120’s first race in America, he was fourth and won his class in a race at Palm Beach, Florida, despite losing his brakes. During 1949 he took the ERA to fifth in the Richmond Trophy at Goodwood though at Jersey’s Road Race, after qualifying second fastest to Luigi Villoresi’s Maserati he frustratingly did not start due to engine bearing failure. He had victory with Forrest Lycett’s Bentley 8 litre in a National race at Silverstone plus reuniting with his ERA he was third in the Chichester Cup and fifth in Goodwood’s Richmond Trophy. The year saw him make his Le Mans debut, with Charles Brackenberry, though they retired their Aston Martin DB2 after 6 laps due to water pump failure but in the following month the pair took second place with it in the Spa 24 Hours. In his following Le Mans entries, he and Bert Hadley retired a Jaguar XK120 in 1950 due to clutch failure after 21 hours while lying third while 1951 saw him and co-driver Clemente Biondetti retire a Jaguar C-Type from third place after 50 laps. Returning in 1952 with a Nash-Healey, he and Tommy Wisdom finished third, behind two factory-entered Mercedes-Benz W194 300SLs, and winners in the 5000cc class, and in his final Le Mans the following year he finished eleventh out of 60 starters with B.Hadley in a Nash-Healey.

1950 saw his only World Championship race though after qualifying twelfth, the supercharger failed during the race and the ERA rolled to a halt, with him having to quickly exit the burning car. Racing an XK120 he was seventh in the Tourist Trophy and eighth in the Silverstone International plus took second place with Forrest Lycett’s Bentley in a Goodwood handicap. The year saw him contest his first Mille Miglia, in one of three works-prepared Jaguar XK 120s, with the company also providing another for four-time Mille Miglia winner Clemente Biondetti. Leslie and co-driver John Lea finished fifth and were the highest placed of the four cars despite his wipers failing, which caused him to borrow his co-driver’s seat cushion to look over the screen to see in the appalling weather. In his three Mille Miglia events over the following years, he reunited with J.Lea and the XK120 in 1951 though an accident put them out. He was seventh in 1952 in a Nash-Healey, with Daily Telegraph motoring correspondent Bill McKenzie as his passenger, though the duo retired in 1953 when racing Jaguar’s C-Type. 1951 saw a fifth place result with the XK120 in the Silverstone International Trophy and in a shared drive in the Tourist Trophy he and Tony Rolt finished fourth in a C-Type. He was to have driven the V16 BRM in the Italian GP at Monza but he was unable to reach the circuit in time for a pre-race test session in the very early morning. Hans Stuck took the drive but the car blew up in practice and did not race.

He set numerous world records with Jaguar sports cars at the Autodrome de Montlhéry, a banked oval track near Paris, and in 1950 averaged 107.46 mph for 24 hours, including stops for fuel and tyres, in an XK120 roadster JWK 651 with co-driver Stirling Moss. This was the first time a production car had averaged over 100 mph for 24 hours and, driving in three-hour shifts, they covered 2579.16 miles, with a best lap of 126.2 mph. In the following year running solo in the XK120 he did 131.83 miles in one hour, with his best lap 134.43 mph, and it was impressive considering he would be facing the g-force induced by 30 degree banking twice every minute, using Forties technology, leaf spring suspension and narrow crossply tyres. However, he remarked that the car felt so good it could have gone on for another week – but his light hearted remark did eventually lead to him, Stirling Moss, Bert Hadley and Jack Fairman attempting this ‘flat out for a week’ challenge in 1952!

Stirling Moss himself recounted the story, telling how Leslie had talked Jaguar into attempting 100mph for a week at Monthlery. “We again drove in three-hour spells. The speedbowl lap was under a minute at 120mph, so it was quite a strain. After each straight we hit the banking high up near the lip, then plunged off, twice every fifty seconds, night and day. In each spell we would cover about 2000 laps. It was impossible to keep one’s mind occupied on a job like that. We had a two-way radio which helped keep boredom at bay. We talked all the time, called each other names, even told stories. One dare not let the mind wander, because we were running within four feet of the banking lip at around 120mph. One had to concentrate on something. I worked out how many million revs the engine made in a day, how many times the wheels turned, things like that. The weather did not help; hot by day, cold at night. Night driving was a strain too, because we couldn’t afford the drain on the battery of extra lights. The headlights had to be set very high to let us see the top of the banking when we were on it, and this meant that on the short straights we could see nothing at all because the beams were playing in the air. We hit several hares, rabbits and birds, and Leslie swore at one point that he’d seen a huge ten-foot tall figure in a long cloak, wearing a tall pointed hat, striding toward him along the verge. Next time round the figure had gone…it worried the life out of him for the rest of his stint. In fact I had donned a Shell fuel funnel, pulled a tarpaulin around me and sat on Jack Fairman’s shoulders as he strode along the verge. After Leslie had whizzed by we ran away and hid…All very childish, but good fun in the circumstances. Leslie then had an extraordinary idea to get his own back during one of my stints. I came whistling off the banking to find him sitting with Jack Fairman in the middle of the track, playing cards! Then he took the pit signal board and put it out on the track, so that my natural line past the pits took me between it and the timekeeper’s hut. He was lounging beside the hut so I waved to him as I shot through the gap. Next time round the board had been moved closer to the hut. The gap was narrower, but I couldn’t leave the fast line so I shot through it again. Next time round, he’d moved the board closer still. Each lap he narrowed the gap which made me concentrate harder to pass through it. Eventually he gave in, and the board went back to its proper position, hung on the tent. At least it passed the time…” During the run the car broke a spring but no spare was carried on board and any outside replacement would make the car ineligible for any further records beyond those already done before the repair. Leslie drove nine hours to save the others from added risk while the speed had to be maintained on the broken spring and when he finally stopped to have it replaced, the car had taken the World and Class C 72-hour records at 105.55 mph, World and Class C four-day records at 101.17 mph, Class C 10,000-kilometer record at 107.031 mph, World and Class C 15,000-kilometer records at 101.95 mph, and World and Class C 10,000-mile records at 100.65 mph. Once the repair was done the XK120 went on to complete the full seven days and nights, covering a total of 16,851.73 miles at an average speed of 100.31 mph.

In 2001, JWK 651 came up for auction and sold for £230,000 ($350,000), making it at the time the world’s most valuable XK120.

In December 1952 he, Moss, rally driver David Humphrey, and navigator John Cutts drove a Humber Super Snipe Mark IV on a journey from Oslo, Norway, to Lisbon, Portugal, a total of 16 countries. The company hoped the trip might be completed in five days but they finished the 3380 miles in 3 days, 17 hours and 59 minutes, despite traffic, sheet ice, blizzards and snowdrifts up to 18 inches deep en route. The team stopped only for meals, refuelling, driver changeovers, and to change a wheel after a puncture and they took every opportunity to cruise at 90 mph (140 km/h). Leslie drove the last three hours to Lisbon at an average of 64 mph (103 km/h). In the following year, Rootes commissioned his ERA company to modify a Sunbeam Alpine for Stirling Moss and Sheila van Damm to drive flat-out through a flying kilometre on a highway in Belgium. Stirling’s speed of 120.13 mph (193.33 km/h) established a new Belgian national record for cars of its class and two days later Leslie drove the car for an hour at an average speed of 111.2 mph (179.0 km/h).

Besides his rallying and record attempts, in 1953 he teamed with Briggs Cunningham for the Reims 12 Hours and they came home third in a Chrysler powered Cunningham C4-R.

As a member of the Rootes factory teams he contested four Monte Carlo Rallies and one Alpine Rally and the Competition Manager Norman Garrad said he “knew more about the geometry of driving than anybody in the business…I used to sit beside Leslie and say, ‘I don’t give a damn who you are, you are never going to get round this one at this speed.’ Thank God he always did.” He was third with a Jaguar XK120 in 1952’s RAC Rally but was later disqualified after a protest for running without rear spats, despite the scrutineers having noted and agreed their removal. He took the team prize at 1953’s Monte Carlo Rally, with Stirling Moss and Jack Imhof, in a Sunbeam-Talbot Mark IIAs and won his class in the Alpine Rally with a Sunbeam Alpine Mark I. He repeated the team prize result in the following year’s Monte Carlo Rally, this time with Stirling Moss and Sheila van Damm, in Sunbeam-Talbot Mark IIAs but during the rally he suffered a heart attack. Norman Garrad, who was in the car with him and navigator John Cutts, said “he somehow persuaded his colleagues..to get to the end of the event before committing him to hospital in Monaco” but he was unconscious when they arrived in Monte Carlo and nearly died that night in the hospital.

Unfortunately, his worsening heart condition forced him to retire from competition in 1954. He bought a farm in Gloucestershire plus continued to run his Maidenhead-based company, Prototype Engineering, which produced precision components for the nuclear industry. He also developed a keen interest in horse racing and owned several racehorses. Leslie passed away in 1959, aged 46, at the family’s home in Foxcote in Gloucestershire. Motor racing photographer Guy Griffiths described him as “Quite the most charming, friendly, unassuming and courteous man in motor racing.” He was also a caring boss, with long term workers at his furniture factory “looked after virtually to the grave. When they became too old for their regular work they might be put onto lighter duties for a lesser wage, but there’d always be something for them, Johnson made sure of that.”