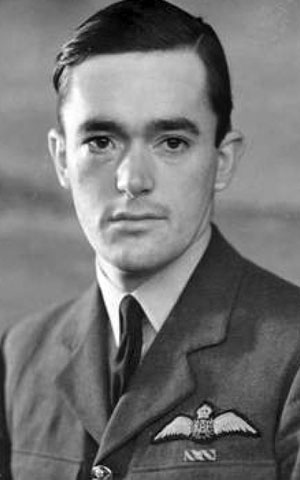

Frederick Anthony Owen “Tony” Gaze, DFC & Two Bars, OAM (3 February 1920 – 29 July 2013) was an Australian fighter pilot and racing driver. He flew with the Royal Air Force in the Second World War, was a flying ace credited with 12.5 confirmed victories (11 and 3 shared), and later enjoyed a successful racing career in the UK, Europe and Australia.

He raced an Alta Formula 2 in Europe for the 1951 season, switching to an HWM-Alta for the following season, planning to racing again in F2. When the sports governing body decided to change the World Championship regulations from Formula One to Formula 2, Gaze’s plans changed as well. He took part in a number of non-championship F1 events, and then in June travelled to the Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps for the Grote Prijs van Belgie. After qualifying the HWM-Alta 16th, he raced one place better, attaining 15th place. By racing in Spa, Gaze became the first Australian to contest a World Championship motor race. This was followed by appearances in the RAC British Grand Prix and the Groβer Preis von Deutschland, although he failed to qualify for the Gran Premio d’Italia. Info from Wiki

Troy Dheahen

Australia’s first F1 driver Tony Gaze.

He was a WWII flying ace, won the Distinguished Flying Cross three times and was awarded the Order of Australia Medal.

Towards the end of the war he shot down a Messerschmitt jet in his Spitfire.

He raced in three Grands Prix in 1952; Belgium, Great Britain and Germany also failing to qualify in Italy.

In 1946 Gaze suggested to Freddie March the Duke of Richmond and Gordon that the around RAF Westhampnett would be a good location for a racing track. Acting on this suggestion, March opened the Goodwood Circuit in 1948.

In the mid 50’s he set up the Kangaroo Stable, the first Australian international racing team. One team member was a young Jack Brabham.

A fighter pilot and Grand Prix driver, he died in his home at the age of 93.

Bio by Stephen Latham

Frederick Anthony Owen Gaze was a distinguished fighter pilot before his motor racing career, flying 485 sorties and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross three times (one of only 47 men in the War to be honoured this way). He contested four F1 World Championship races with his own HWM-Alta in 1952 and became the first Australian in the championship. In 1953, he was a member of the first ever Australian crew at the Monte Carlo Rally and, not content with fighter planes and racing cars, 1960 saw him compete in the World Gliding Championships.

In 1914 his father, Irvine went to the docks at Port Melbourne to bid farewell to his cousin, who was a member of Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. He was to be the chaplain/photographer but at the last minute the team found themselves a man short and he asked Irvine if he would like to join them. A few hours later they set off to Antarctica in their ship, the Aurora, and later set up camp in a base that Robert Falcon Scott’s party had established a few years earlier. Their job was to trek inland and establish depots for the main expedition to visit after they had passed the South Pole. They successfully did this but the ship broke free from its moorings and drifted away and the team spent two years living on the leftover supplies of Scott’s expedition, seal meat and penguin eggs. His cousin died but the rest of the party was finally rescued. Irvine later served in Europe in World War I in the Royal Flying Corps in 1917 and at the end of the war he and his wife travelled back to Melbourne, where Tony was born on the 3rd February 1920.

Tony and his brother Scott attended Geelong Grammar School then left to study at Cambridge in the UK though had not been there long when World War 2 broke out. They followed in their father’s footsteps and became fighter pilots, joining the Royal Air Force, and after completing his training on Spitfires Tony joined No 610 Squadron at Westhampnett, near Goodwood. Scott also joined a squadron at the same time but while only aged nineteen was sadly killed when his Spitfire was shot down in 1941. Tony flew his first mission in 1941 and was eventually credited with downing at least 11 enemy aircraft. In 1943 he was shot down over France and despite suffering head injuries spent almost two months evading capture with the help of the French Resistance. In the latter days of the conflict he became the first Australian to shoot down an enemy jet plus the first Australian to fly the Royal Air Force’s first jet fighter, the Meteor, in combat. On top of the three DFCs received, he was also awarded the Defence Medal, the War Medal 1939-1945, the Air Crew Europe Star and the 1939-1945 Star.

While at Cambridge before the war, he borrowed an uncle’s Hudson to drive at Brooklands but being a beginner had to have a passenger to tell when the faster cars were coming up behind along the banking. He described how “we didn’t get very far due to fuel vaporising as the fuel pipe ran alongside the exhaust. Later in the Motor or Autocar it said that the other American car, a Terraplane, was flagged off and they were thinking of flagging me off as well for dangerous driving.” When not flying, Tony and another pilot, Dickie Stoop, enjoyed racing MGs around the Westhampnett airfield, which was within the Goodwood estate owned by the Duke of Richmond. He told how the airfield “was just four big paddocks joined up to make a grass airfield on the Goodwood estate. Tar was put across the grass but there was still a worry that the aircraft refuelling tankers would get bogged. It was Douglas Bader’s idea to build a perimeter track…After the war I was in Charles Follett’s office, as was the Duke of Richmond. He was president of the Junior Car Club and looking for a replacement for Brooklands. I heard they were looking at airfields and I said, “Don’t be silly, he’s got one.” Then someone said “Go and tell him.” On encountering him he asked “When are we going to have a race around Westhampnett?” He said. “What!” Then I said that we had been racing round and it’s a great circuit. He said. “Bless my soul, what would the neighbours say?” He hadn’t thought of it as it was part of his home. So that was the start of Goodwood.” It was eventually transformed into a racing circuit and on September 18 1948, Goodwood Motor Racing Circuit staged its inaugural motor race meeting; at which a young Stirling Moss won the 500cc F3 event.

After leaving the RAF he returned to Australia, taking a pre-war Alta racing car with him, and while there started racing. He successfully raced at Melbourne’s Rob Roy hillclimb plus took part in 1948’s Australian Grand Prix at the Point Cook Aerodrome, a Royal Australian Air Force base just outside Melbourne. The circuit utilised the base’s runways and service roads, over 42 laps of a 3.85 kilometre circuit, and was staged as a handicap event with the first car starting eighteen minutes before the last. Unfortunately conditions were oppressive, with the temperature topping 38 °C by mid-morning plus there were hot winds buffeting the exposed pits on the start/finish straight. The overpowering heat and the bumpy concrete surfaced runways took a heavy toll on the drivers and cars. Tony retired from the race though besides mechanical retirements, several drivers had to retire due to heat exhaustion.

In 1949 he married Kay Wakefield and the couple eventually returned to Britain, where he served briefly with No 600 Squadron of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force, again flying Meteors. He bought an Alta Formula 2 car for 1951, which he raced in Europe, finishing twelfth at Monza, eighth at Genoa and Nurburgring, though retired at Avus and Caracalla (Rome). He then planned to continue in F2 races in 1952 but the regulations for the World Championship were changed that year, from F1 to F2, so he decided to compete. In June he travelled to Spa for the Belgian GP, becoming the first Australian to compete in an F1 event and finished fifteenth on his debut. He retired from the British and German races in July though speaking later of the Nurburgring, he declared “I liked it, it was like Bathurst only longer..You never got a lot of practice there because a lap took nine minutes, but I knew it well from the books that I’d read, it was frightening but wonderful at the same time. I remember there being a hedge the whole way around. I didn’t realise that photographers used to hide in the hedges to get the best photos, on my first couple of laps I gave some of them the fright of their life!” He didn’t qualify for the Italian race at Monza but nearly took out Ascari while there. He said that during practice “I saw him coming up behind me going round the Curva Grande and thought if I could still be in front after the second lesmo I would get a tow down the back straight and possibly stick with him around the South Curve and get another tow. So I went flat through the second lesmo, got the whole thing sideways and nearly took him with me. He gave me a bit of a look as he went by, so when practice finished I sought him out and said I was terribly sorry. He slapped me on the back and said, “Ahhh! Think nothing, we now go and have a cup of tea.” So he took me off and bought me a cup of tea. Every time I saw him after that at a race meeting he would slap me on the back and say “Have a cup of tea?” I don’t think anyone apologised to him before but I thought you couldn’t take the world champion out like that.

Competing in non-championship F1 events, he was sixteenth in the International Trophy at Silverstone, fifth in Goodwood’s Lavant Cup, fourth in the National Trophy at Turnberry. He was sixth at Goodwood’s Easter Meeting though retired from the Newcastle Journal Trophy at Charterhall while racing a Jaguar XK120 he was fifth at the Silverstone International and second at Snetterton with a Maserati 8CM.

Although the reliability of the Alta engine was a concern for Tony he faced difficulty in finding a competitive car for the 1953 GP season. Enzo Ferrari was willing to sell him a Ferrari 500 but without works support it would have been a very expensive proposition, so he turned to sportscars. However, before this, January saw him contest the Monte Carlo Rally with team-mates Lex Davison and Stan Jones, both well known motor sport figures in Australia. Driving a 1951 Holden 48-215 (the Australian marque’s first model and in its competition debut), the trio started in Glasgow and at one point were running in the top 10, but finished sixty fourth of four hundred entrants. He was invited to be part of a test of the Aston Martin DB3 at Monza, which took place in the snow! After flying there he was collected at the airport by Peter Collins, who proceeded to frighten the life out of him by driving the Lagonda on the ice and getting it sideways. Following the test he and Graham Whitehead were offered cars but he recalled “We were promised that Aston Martin wasn’t going to come out with something new to make us obsolete the moment we got these things. So the first race meeting I go to Reg Parnell turns up in a works DB3S which was a lot lighter and more powerful!” He and Grahaham Whitehead travelled to the Cote d’Azur for the Hyeres 12 Hours in June, held on a 7km road course, but though at one point they were running fifth in the pouring rain they retired after two hours with a broken timing chain. The pair were fourth in the Tourist Trophy at Dundrod, then he and Tom Meyer raced the car in the 12 Hour Pescara event. Tony had a lucky escape from a crash in the Portuguese GP at Oporto when he was hit by a Ferrari on lap 3, which catapulted him into a tree. Fortunately he was thrown out of the car, as the Aston broke in half and burst into flames, and he was left semi-conscious in the middle of the road ten metres from the remains of the car, which was completely destroyed. Spectators rushed onto the track and carried him to safety, with his only injuries being cuts and bruises.

Unable to obtain a works Aston Martin or a Jaguar he then approached HWM and in early January 1954 travelled to New Zealand with a supercharged GP HWM Alta 2 litre. At the New Zealand GP at Ardmore, the field included drivers such as Ken Wharton (BRM), Peter Whitehead (Ferrari 125), Horace Gould (Cooper-Bristol) and Stan Jones (Maybach Special) plus a young Jack Brabham in a Cooper-Bristol, though it would end in controversy. Once the race was underway, he was running fifth, behind Wharton, Whitehead, Jones and Gould after 10 laps then on lap 27, Horace Gould came in for a pit-stop which was again the subject of later dispute. According to observers on the spot, he lost a place only to Tony though according to the official record he dropped a whole lap and was back to eight or ninth place. Towards the end of the race, attrition had reduced the field down to 16 competitors, with Stan Jones out in front though on the 76th lap a burst of speed brought Tony up to second and Horace to fourth. Horace was forced to stop for fuel on the 81st lap and Tony in the 92nd, which saw Ken Wharton up into second place again and for the remainder of the race he held his lead. The closing laps narrowed the gaps and they crossed the line with S.Jones taking victory, followed by K.Wharton, Tony and H.Gould. However, Horace claimed, and was supported by his pit crew, that he had run 101 laps and finished first and the protest was entered and upheld by the stewards. He was moved up to second place though Ken and Tony then protested but Horace said that either he had won or he was fourth, he could not have been second! There followed a lengthy enquiry that lasted several weeks but in the end the placings were reverted to the original finishing order, with Horace relegated to fourth and Tony was second. Soon after came the Lady Wigram Trophy, at Wigram Airfield near Christchurch, where he started third on the grid, alongside K.Wharton’s BRM and P.Whitehead’s Ferrari. He eventually finished second to Whitehead although Wharton had had most of the race under control until the car eventually quit short of the finish line. He physically pushed the heavy BRM a quarter of a mile over the line, encouraged by the BRM mechanics, just before the fourth placed car commenced its last lap.

Tony was able to sell the car before returning to Europe though before this, at the end of January he competed in the Mount Druitt 24 Hours Road Race in New South Wales, Australia, teamed with Peter Whitehead and Alf Barrett in a Jaguar C-Type. This was an endurance race for production cars, organised by the Australian Racing Drivers’ Club and was the first motor race of 24 hours duration to be held in Australia. The cars were required to be stock models, competing as purchased with no modifications permitted other than the removal of the silencer. All the starters finished the race, with Tony, Alf and Peter coming home sixteenth, with those that had retired rejoining to cross the finish line at the end of the 24 hours. At the end of May he raced an HWM at the Aintree International, finishing fourth behind Duncan Hamilton’s Jaguar C-Type, Carroll Shelby’s Aston DB3S and Jimmy Stewart’s C-Type. This was followed a week later by the Hyeres 12 Hours, near Toulon in France, where he teamed with George Abecassis in the HWM Jaguar. Although Trintignant and Piotti were favourites in a Ferrari, the HWM ran firmly in second position despite a fractured water pipe which required frequent stops for water. Unfortunately, despite a consistent performance, towards the end of the race the officials felt that the car had taken on more water than the regulations allowed and disqualified them. He and Graham Whitehead were seventh in the 12 Hour Reims, with had featured a Le Mans style start, but it was a memorable race for Tony. After a midnight start in pouring rain, he recalled how “after a few laps I was coming down the main straight, started braking only to find myself slithering down the escape road half way to Reims. Next lap I did it again then realised that I couldn’t see properly due to a gearbox oil leak. Using caster oil, the more I wiped my goggles the worse it became. I took them off and kept going. At the end my eyes were like two pieces of steak and I was given antihistamine by a doctor who told me not to have a drink afterwards. My eyes cleared up, but I had a drink at dinner that night. Sitting opposite Carroll Shelby I got halfway through my soup when I went blump with my head falling into the bowl. For the rest of the season whenever I saw Carroll he said “I’ll always remember you as the guy who put his face in the soup to drink.” He then contested a non championship British GP in July, followed in August with a victory at Crystal Palace, from pole. Then came Zandvoort, though he failed to finish after a huge spin on the circuit but after trying a shortcut to the other side the grass was so wet his car became bogged and when he stopped he could see Duncan Hamilton in the pits overcome with laughter at his predicament. The end of August saw him at the French seaside resort town of La Baule to contest the sportscar handicap race, where he finished sixth. Following this he shared the car with John Riseley-Pritchard in the Tourist Trophy at Dundrod though with 9 laps of the course completed a dropped engine valve would end their race. He was lucky to escape uninjured at Goodwood at the end of September in the Jaguar powered HWM when at one point he told how “Whatever the reason it wasn’t going to stop so I spun it down the escape road and hit the eight feet high dirt wall and got tossed over the top of it and ended up in the crowd.” A Motor Sport magazine report stated ‘Practice was notable for Tony Gaze ground-looping the HWM Jaguar when going too fast into Woodcote Corner, thereby bruising himself’. The car was a write off but he told how “they salvaged what they could of it-the engine and things-and put the rest of it up against the factory wall ready to try and straighten it and sell it to some unfortunate bloke. But the scrap metal man arrived and took it without asking!”

He then acquired an ex-Ascari Ferrari 500 F2 car and went on to compete in non-championship European races in 1955 but before this, th early part of the year saw him back in New Zealand, where he was third in the GP at Ardmore, behind Prince Bira and Peter Whitehead. On his return to England he and a number of other Australian racers, David McKay, Tom Sulman, Les Cosh, Dick Cobden and Jack Brabham, formed the Kangaroo Stable, initially to race sportscars in Europe. In late 1954 Tony had tried buying D-type Jaguars for their team but when he couldn’t get a firm delivery date he struck a deal with Aston Martin’s John Wyer for a trio of DB3Ss for the start of the 1955 season. The Kangaroo Stable’s first race came in May at the 12 Hours Hyeres in France and they finished second, third and fourth, with Tony and D.McKay in the second placed car. Tony raced the DB3S at Snetterton and finished eighth at Porto, though retired at Monsanto and at the Goodwood 9 Hours due to distributor problems. After the tragedy at Le Mans that year, the ensuing dearth of sports car racing resulted in the Kangaroo Stable’s disbandment later in the year. He had two further HWM drives that year, first at Oulton Park’s British Empire Trophy in April though he failed to qualify for his heat due to gearbox issues and retired at Silverstone in the September.

Tony had promised his wife that he would retire and said he would hang up his helmet after the next season’s New Zealand and Australian races. In the new year, he and Peter Whitehead raced Ferrari 500/625s in the New Zealand GP at Ardmore on 7th January. Besides the duo, the English contingent in the race included Reg Parnell in an Aston Martin, Leslie Marr with his Connaught and Stirling Moss, whom everyone expected to win in his Maserati 250S. There was drama before the race even took place as several cars were sent to Wellington instead of Auckland due to a shipping mistake. This included the two Ferraris plus Moss and Marr’s cars and cases of spares for all the cars were still missing the day before the race, though most turned up. During the main practice day R.Parnell’s Aston Martin threw a conrod through the side of the crankcase and it seemed he would be a spectator at the event though in a very sporting gesture P.Whitehead lent him his second car, a Cooper-Jaguar. On race day, pole position was held by Moss, followed by Whitehead, Tony and Brabham though just after the start, Tony took the lead closely followed by Moss and Whitehead. Later in the race Moss was leading and appeared unchallengeable though he started losing fuel but despite this he managed to take the flag, with Tony creeping up by the end and his was the only car on the same lap. He was second in the Lady Wigram Trophy, behind P.Whithehead though ahead of L.Marr and R.Parnell, and he finished off the month with victory at a Dunedin Road Race event, bringing his Ferrari home ahead of Parnell’s Aston. In the following month he was second to Whitehead in a Road Race run over forty-one 5.87km laps of a course laid out around Ryal Bush in New Zealand’s South Island. Back in the the HWM Jaguar, he competed in two events at Albert Park in Australia, with March seeing a victory at the Moomba TT, a race for open and closed sports cars, and he followed this with third place in the Argus Cup.

To his wife’s relief, he sold his cars to Lex Davison but was then asked by Dicky Stoop if he would drive a Fraser Nash Sebring at Le Mans. During the race, he initially faced problems with his goggles being blown off due to the wind of the deflector blowing over the top of the screen into his face. Then during the night the engine stopped and he pulled over “to take the cap off the tank and then realised that I would have broken the seal. Using my flashlight I could see that the fuel line had broken off at the pump. It was too far to push but I managed to get back by pushing the pipes together, filling the bowls, driving for a few seconds and then doing it all again. Luckily we had a spare pipe but back in those days all the spares had to be carried within the cars and laid out along the pits prior to the race. Dicky went again but after his stint he didn’t come in. He had lost concentration and flew off through the esses” and their race was ended after 100 laps.

Tony retired in 1956 and took up farming and salmon fishing until developing a passion for gliding, after a chance conversation with avid glider competitor Prince Bira. He became an active member of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Gliding Club and went on to represent Australia in the 1960 World Gliding Championship at the Butzweiler airfield, near Cologne in Germany. Sadly, his wife Kay died in 1976 and he returned to Australia, selling their home, Caradoc Court, which went on to become a hotel. He later married Diana Davison, widow of Lex (who tragically died after suffering a heart attack and crashing at Sandown in 1965) and the couple became well known in the historic motor racing world. In 2005 they were special guests of Lord March at the Goodwood Revival meeting and several years later Tony and Diana returned to Goodwood for the 2010 Revival, which marked the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Britain. In 2006 he was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia in recognition of his outstanding achievements and service to the Commonwealth. Living on a farm in rural Nagambie, he focused on farming and raised cattle and had crops though sadly, Diana died in 2012. Tony himself passed away on the 29th July 2013 in Geelong, Victoria and a memorial service was held in the Geelong Grammar School Chapel, giving members of the public the opportunity to honour an amazing, accomplished man. A Spitfire from the Temora Aviation Museum flew over the memorial service and its president David Lowy said “It is an honour for the Museum to be involved in the memorial service for squadron leader Tony Gaze. He made significant contributions to the war effort, flying Spitfires with the Royal Air Force, and he finished World War II as one of Australia’s most decorated fighter aces with 11 destroys and 3 shared to his name.”

In 2009, Tony’s story was told in the book, ‘Almost Unknown. The Story of Squadron Leader Tony Gaze OAM DFC : Fighter Pilot and Racing Driver’, telling of his extraordinary life and remarkable achievements.

+

Further to my post /FB page “forgotten”/ on Tony Gaze, I recently came across some articles about his home in the UK, Caradoc Court, and his gliding activities. The information regarding the Monte Carlo Rally came from a Eoin Young article in Motor Sport plus a primotipo website.

As mentioned, Tony was a distinguished fighter pilot and towards the end of the War he was involved in defending against the V1 flying bombs. Tony and other pilots would intercept them over the Channel, flying alongside with the wingtip just under the tip of the V1, then flip them into a spin so that they would crash harmlessly short of its target.

Tony’s racing exploits after the War would see him compete in the UK, Europe, Australia and New Zealand plus also contest 1953’s Monte Carlo Rally. John Barraclough (an Australian racer and Hill Climb Champion) was entered for the Rally but had also arranged an entry for Lex Davison and Stan Jones. After he and Tony met at London’s Steering Wheel Club, Tony became the third member of the crew and he sorted all of the paperwork and arranged getting the car through Customs. Their car for the event was a Holden 48-215 and with all the luggage, spares, equipment and three drivers on board it weighed 8 hundredweight more than the standard car. A kangaroo, with Australia written underneath, was painted on either side of the bonnet and ‘Australia’ written on the bootlid in gold, which apparently was the new Registered Australian Racing Colours of green and gold. Competitors came from over 20 different countries and could choose to start from different cities in Europe, including Glasgow, Stockholm, Oslo, Monte Carlo itself, Munich, Palermo and Lisbon. The trio started their journey from the Royal Automobile Club of Scotland and their 2100 mile route to Monte Carlo would incorporate Wales, London, Lilles, Brussels, Amsterdam, Paris and Clermont Ferrand in The Alps. They encountered continual thick fog in the first three days then falling snow and icy roads in the Alps although Motor Sport magazine described the conditions as kind. However, the driving conditions caused them to abandon their sleeping roster to make use of Tony’s skill in fast driving in fog. At one point while Stan was driving through the ice, as they overtook a lorry it veered and hit the side of the car inches from Lex’s sleeping head but he continued sleeping peacefully. The trio eventually reached Monaco and of the 404 cars which started the Rally, they were one of the 253 that finished without loss of points. They were escorted to a marquee on the Boulevard and were offered drinks and Lex Davison recalled “we stood beside the sea wall sipping brandy, blinking in the sun. We were terribly tired and I noticed that Tony was fast asleep standing up leaning against the sea wall.” Then came acceleration and braking tests and ninety eight cars would qualify for a final, eliminating, regularity test. This was a 46 mile run over the Col de Braus above Monaco but though the experienced crews knew the route, Tony, Lex and Stan did not. Many of the others also had a spare car to use to practise it but the trio were only able to do one lap later in the day as passengers in a VW. The rally was won by Maurice Gatsonides and Peter Worledge’s Ford Zephyr (M.Gatsonides had spent four weeks previous to it lapping the Col de Braus route) and the Australian team finished in 64th place. Following the rally they took the Holden to Monza and as Tony knew Giuseppe Bacciagaluppi, the manager of the race circuit, he allowed them to take the car onto the track. With the three drivers on board, they averaged a higher lap speed than the road tested maximum for a standard Holden. They eventually drove back through Switzerland to England and from there Tony shipped the car back to Australia. Lex and Stan were later invited to a luncheon at the Holden headquarters, where they were each given a new Holden FJ though it was said Tony never received anything.

Tony also became actively involved in gliding. He and his wife Katie lived at Caradoc Court, near Ross-On-Wye and the house was just across the river from the Bristol and Gloucestershire Gliding Club, which he soon joined and became an active member. In May 1960 he set a UK two-seater 200km triangle speed record with Rosemary Storey and in June 1961 they set a UK out-and-return record of 170 miles (about 280km). He took part in a number of gliding competitions with some success and represented Australia in the World Championships at Butzweilerhof in 1960. He also acted as host to the Australian team at the South Cerney World Championships in 1965. He was remembered for his unselfishness and unassuming manner and although clearly a very wealthy man, it did not show in his manner. Amusingly, at one event, when his retrieve car broke down, the public address system asked if a member of his crew would ‘bring his other Jaguar’. Tony bought an Auster Tugmaster plane in which he used to fly to the gliding club from an airstrip on the Caradoc estate. He provided countless tows for members with it (and with a later plane) when the club’s tugs were not available, often missing the chance to glide himself in order to help other people into the air.

After Katie died in 1976, the house was sold and he returned to Melbourne. Caradoc Court was badly damaged in a fire in 1986 although it was eventually fully restored and was used as a hotel. At a later sale of items, a Nelco Solo car (an electric invalid carriage) was auctioned, which had been stored for many years in a barn and it was said that Tony used to tear around the house’s gardens in this vehicle! Tony sadly passed away in 2013 and after memorial services in Australia, his ashes were to be scattered at Goodwood.